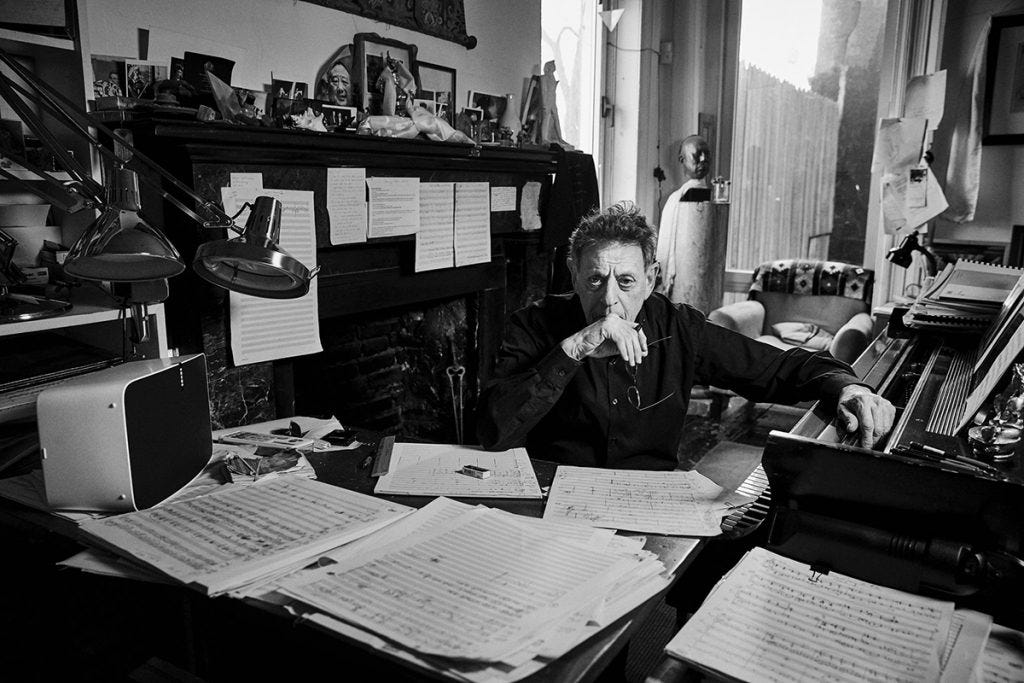

Philip Glass in Dialogue: Reflecting on Music, Bowie, and Bridging Genres

A Journey through Symphonies and Conversations, Glass Explores the Intersection of Popular Culture and Concert Music

Hello and welcome to "Vintage Cafe," a reader-supported newsletter crafted for curious minds. It's my personal haven where I share my passions: music, films, books, travel, coffee, and art. To stay updated on new posts and to support my work, consider becoming either a free or paid subscriber. Opting for a paid subscription is the most impactful way to sustain and champion Vintage Cafe.

If there's one thing certainly not lacking in music from any era, it's controversy—from Beethoven's "Eroica" to Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" to the seductive hip movements of Elvis Presley or the outbursts of the Sex Pistols in the punk era. In classical music, this role has often been attributed to a small group of contemporary composers known as "minimalists," among whom Glass is one of the most prominent. The term comes from a simple description of the features that adorned their music, namely the use of repetitive melodies and cycles as well as minimal musical means. These composers, with their music, provoked fierce reactions and debates within the musical establishment, inevitably leading to their isolation.

The minimalists themselves emerged from the creative worlds of the New York downtown scene in the 1960s and began performing not in traditional concert halls but in art galleries and lofts. Their music differed from that of their European counterparts; it was not baroque but raw and experimental. It was described as minimal because every note, every gesture, and every statement had a precise purpose.

Despite all the debates about the value of Glass's music and that of his contemporaries, he simply changed the course of modern music. Thanks to him, boundaries were erased, inspiring many similar and authentic figures on similar journeys, people like David Bowie, Brian Eno, Laurie Anderson, Mike Oldfield, and collaborating with diverse individuals such as Leonard Cohen, Aphex Twin, David Byrne, Mick Jagger, and Paul Simon. Even the song "Where the Streets Have No Name" by U2 is inspired by Glass's characteristic melodies.

However, Glass's status is primarily due to his enormous body of work, work ethic, and consistent array of performances. At the time when this interview was conducted in 2019 in Malmo, Sweden, there was an avalanche of activities and performances. Coincidentally, January 31st marks composer Philip Glass' birthday, and to celebrate, I'm republishing this interview. Around that time, his symphony, "Lodger," based on David Bowie's album of the same name, premiered in London. Later in Paris, a "Philip Glass weekend" was organized, during which numerous artists, including Anoushka Shankar, performed his works. The next city was Barcelona, where he performed with two classical pianists, Maki Namekawa and Anton Batagov. Parallel to these performances, his operas "Einstein on the Beach" and "Akhnaten" were staged in Germany and the Netherlands. Despite all these performances and presentations, he had a short tour in Sweden with his Philip Glass Ensemble, marking the 50th anniversary of the ensemble's existence. After the rehearsal in Malmo, I had the rare opportunity to interview this modest man, who, in a short time, provided valuable insights into his work. The performance that evening was truly breathtaking, and I must emphasize the privilege of witnessing a composer personally perform his own music with the Ensemble.

With this short tour in Sweden, you will celebrate the 50th anniversary of your ensemble, the Philip Glass Ensemble. What makes this ensemble so special for you, especially since, during your career, you expanded into other fields and formats: operas, symphonies, string quartets, and solo piano?

We didn't keep track of how much time had passed at all. The people who organized these concerts told us that 50 years had passed, and we counted and said yes, that's true. We started working in 1968, initially doing concerts with saxophonist Jon Gibson, who is still part of the ensemble. The ensemble was formed next. 50 years passed without us even noticing.

In the beginning, when I founded the ensemble, it was very difficult to sustain. It's probably the hardest job in the world. I decided not to allow anyone else to play this music except the ensemble because I felt if I had a monopoly on this music and if the music became popular, there would be more work for the ensemble. So, at the beginning, for a full 10 years, the ensemble was the only one performing this music. After the first concert, I started paying the musicians, which meant that there often wouldn't be money for me. However, after the success I achieved with the operas, the ensemble had been performing this music for 10 years, and during that time, it became the best interpreter of this music. That was the most important reason for keeping the ensemble. In the beginning, they were the only ones who wanted to perform this music, and then they became the best at it.

But the music we are performing on this tour, for the most part, was written in the 1980s. There is no other music for the ensemble written after that period. This music, I would say, in some way reveals itself to each new generation. Your generation probably discovered it 20 years ago, and now there are people who are 25 and discovering it for the first time. The most interesting thing about this music is that it seems to survive every new period very well. It seems like it's new at this moment. I think that's because it seems important to people in those different periods. Probably that's the case. But I think it didn't influence anyone. It didn't change the history of music, in my opinion. However, from my perspective, it changed my history, as well as that of the listeners, but not as part of some evolutionary wave in a certain period.

By writing operas, I went in my own direction and never returned to writing that type of music. But we never stopped performing because people like this music. And that's interesting. For the music we are performing here in Malmo, I don't feel like it's old music. It's interesting, and I often wonder why. We often perform our music in front of mixed audiences. There are always many older people, but also many young people. I kept the group together all this time, and in the meantime, many young people appeared who started playing it on the piano or came from the world of opera and theater. We, on the other hand, don't record this type of music anymore. Usually, others are doing it now. But we are happy when we perform it. I am surprised that many young people like to listen to it. Why not from the other side?

Dialogue is one of the fundamental aspects of composing new music

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Vintage Cafe to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.