Welcome to Vintage Cafe—a thoughtfully curated space for lovers of music, film, books, art, travel, and coffee. Each edition offers in-depth reviews, insightful explorations, and hidden gems you won’t find anywhere else. If you enjoy this content and want to support my work and independent writing, the best way is by taking a paid subscription. Your support unlocks exclusive content and keeps this space thriving.

Paris, the city of lights, has long been a muse to artists, but the Paris that we know today didn’t always exist. It was not always a city of grand boulevards, romantic cafes, and an aura of sophisticated beauty. In the mid-19th century, Paris was a much different place—dark, crowded, and plagued by epidemics. The city’s infrastructure was medieval, narrow alleyways crammed with people, and its streets were often impassable.

But then came the great transformation. Napoleon III’s ambitious vision for the city’s renovation, under the guidance of urban planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann, reshaped Paris into a modern metropolis. This transformation became a pivotal moment, not just in urban development but in art history.

Walking into the Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s new exhibition, New Paris: From Monet to Morisot, is like stepping into the heart of a city that has long been an emblem of transformation. It’s Paris in its most radical phase of change, the mid-19th century, when the old, chaotic city was demolished and rebuilt into the Paris we recognize today — wide boulevards, elegant buildings, and green parks.

The city’s modernist reimagination under the direction of Baron Haussmann was not only a feat of architecture but also a social and cultural upheaval. This shift from a medieval slum to a gleaming metropolis is beautifully captured in over 60 works of art, complemented by prints and photographs that shed light on both the romance and the reality of this new Paris.

This exhibition serves as a lens through which we view Paris’s transformation from both an artistic and social perspective. New Paris takes us back to a time when Impressionism was just beginning to take shape, with artists like Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas finding inspiration in a rapidly changing cityscape. What strikes you immediately is how the city’s transformation is as much about its people as it is about its buildings.

Paris: A City in Flux

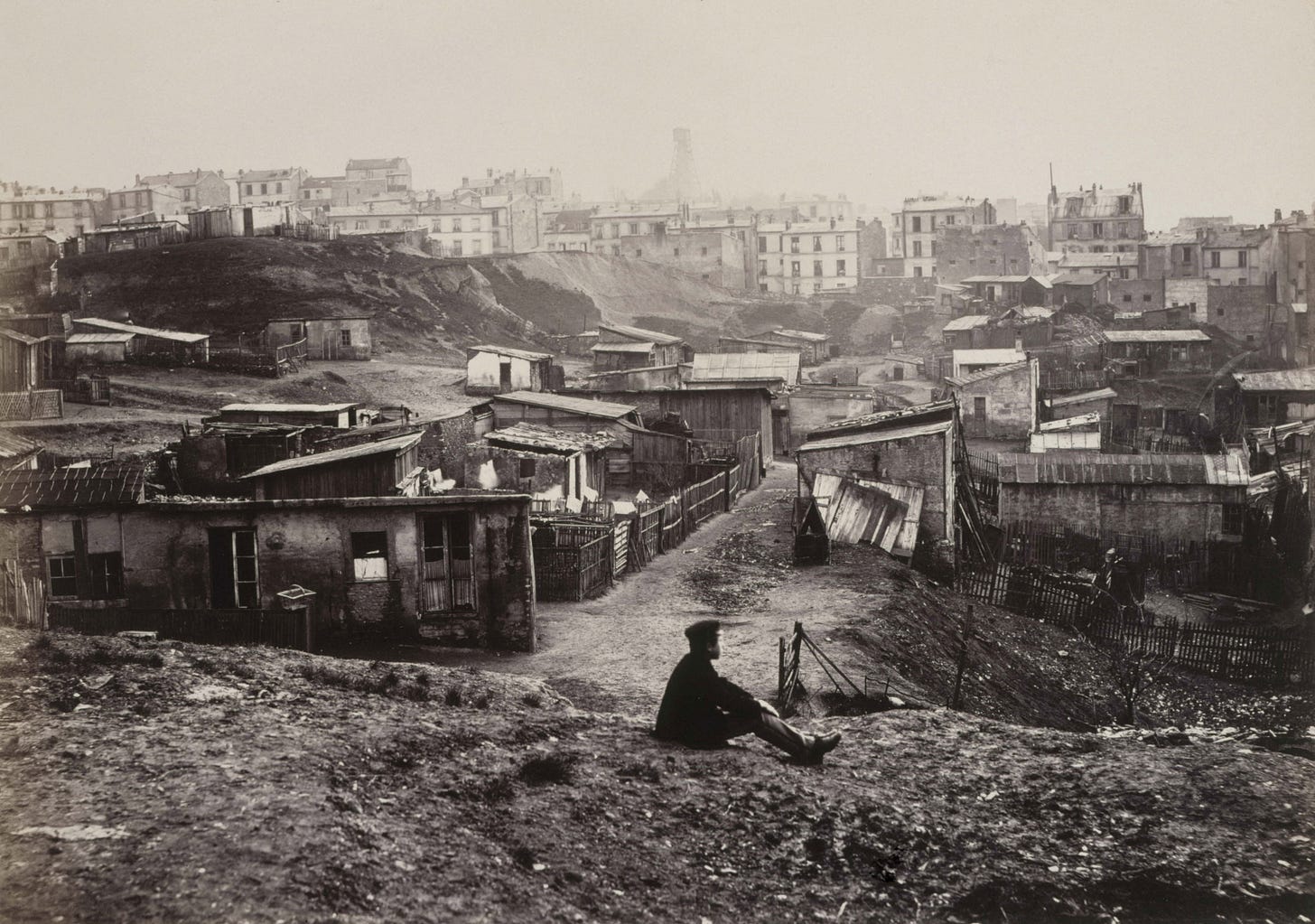

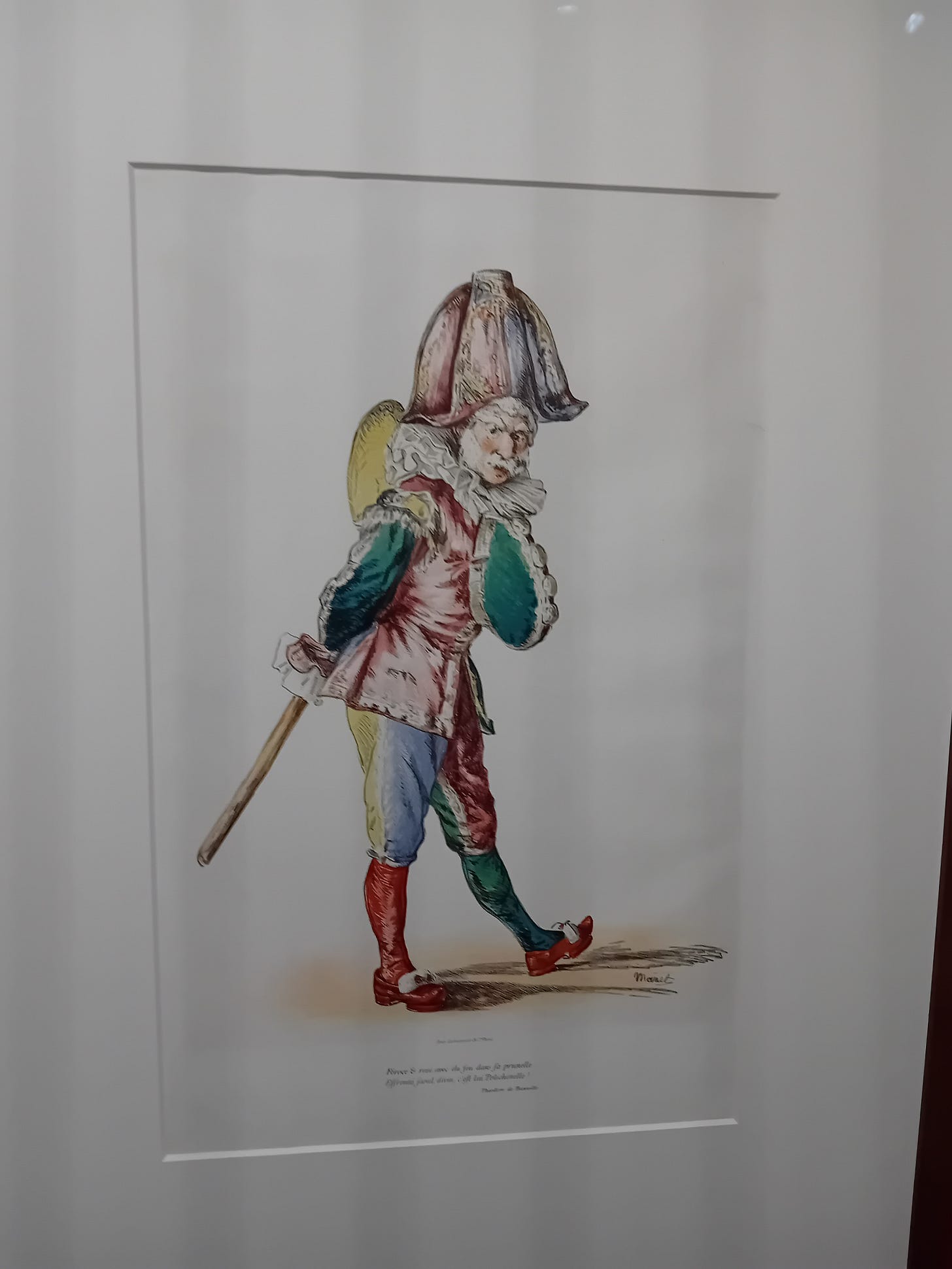

Before Haussmann's grand renovation, Paris was anything but the refined and romantic city that tourists flock to today. It was a city in crisis. The population had exploded to over a million, and its infrastructure was buckling under the pressure. Narrow, winding streets were a breeding ground for disease, and outbreaks of cholera were a constant threat. The working class lived in cramped, squalid conditions, while the aristocracy and bourgeoisie inhabited more spacious quarters, often overlooking the impoverished masses. In his satirical caricatures, Honoré Daumier captured the social divide with biting humor, showing the stark contrasts between the upper class and the working poor. His works are included in the exhibition, offering a visual commentary on the disparities that were both a symptom and a consequence of the changing city.

Charles Marville, Haute de la rue Champlain (vue prise á droit), ca.1877, Museé Carnavalet

But with Napoleon III at the helm, and with the visionary urban planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann leading the charge, Paris underwent one of the most ambitious urban overhauls in history. Between 1853 and 1870, Haussmann oversaw the demolition of over 20,000 buildings and the creation of new boulevards, parks, and modern infrastructure, setting the stage for a city built for the modern world.

At the heart of this transformation was the expansion of Paris to include new neighborhoods like Montmartre and Belleville, neighborhoods that were later immortalized in Impressionist works. These working-class areas were swiftly transformed by Haussmann’s urban planning, yet they remained places of social tension. Many of the city’s poorest residents found themselves pushed to the margins, both physically and socially, as rents skyrocketed, and the city’s elite moved into newly developed areas. The exhibition does a remarkable job of showing the contradictions inherent in this transformation.

Impressionism: The Birth of a New Vision

While Haussmann’s renovations reshaped the physical city, a parallel revolution was taking place in the world of art. The Impressionists, including artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, and Berthe Morisot, were among the first to truly capture the spirit of the new Paris. Their works in the “New Paris” exhibition reveal how the city—now bathed in sunlight and transformed by modernity—became a subject of great fascination and inspiration.

In the heart of the exhibition, one can admire three stunning paintings by Claude Monet, which were painted from the balcony of the Louvre in 1867. These are some of the earliest examples of Monet’s iconic cityscapes, where he turned his back on the classical masterpieces inside the museum to capture the bustling city life outside. These paintings offer us a glimpse of Paris in transition—a city filled with life and energy but also one where change was visibly underway. Monet’s use of light and color not only highlights the transformation of the city but also the new artistic freedom that emerged with Impressionism.

Monet’s cityscapes are part of the larger narrative of Impressionism, a movement that sought to break from the rigid academic traditions that had previously dominated the art world. The Impressionists were more concerned with capturing the fleeting moments of everyday life in Paris—whether it was a group of people sitting in a café, a woman strolling through the park, or the reflections on the Seine. This focus on the present moment, on the experience of life as it unfolded, was revolutionary. The new Paris, in all its grandeur and imperfections, became the perfect subject for these artists.

Women in New Paris: Morisot and Cassatt

The presence of women in the Impressionist movement is a theme that New Paris explores with care. The exhibition dedicates a significant portion to Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, two of the most important female artists of the period.

Among the giants of Impressionism, Berthe Morisot holds a special place. As one of the leading women artists of the movement, she faced a number of societal obstacles that her male counterparts did not. The exhibition features several of her works, showing how she captured not only the changing city but also the role of women within it. Morisot’s delicate and intimate portrayal of women in everyday life offers a different perspective on Paris—one that reflects both the joys and limitations of her time. Her work, often centered on domestic scenes and portraits, was revolutionary in its ability to convey a deeply personal view of Parisian life.

Berthe Morisot, Au bois, 1867, pencil and watercolour on paper (detail). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Morisot, along with fellow female artist Mary Cassatt, was part of the “Trois Grandes Dames de l’Impressionisme.” While Morisot’s work is celebrated for its light touch and sensitivity, it also speaks to the constraints placed on women in Paris during the 19th century. Women like Morisot were often confined to domestic spaces, and yet she found a way to capture the evolving landscape of Paris and the changing role of women in society. Her painting The Cradle (1872), for example, is a tender depiction of a mother looking after her child, reflecting the delicate balance between personal intimacy and the broad social changes occurring around her.

Mary Cassatt, Herfst, portret van Lydia Cassatt, 1880, olieverf op doek, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Pariss

Mary Cassatt, an American-born artist, also played a pivotal role in the development of Impressionism, particularly in the United States, where she introduced the movement to American audiences. Cassatt’s works in the exhibition, such as Autumn, Portrait of Lydia Cassatt (1880), reflect the evolving roles of women in Paris during the time. The Parisienne, with her fashionable attire and presence in new public spaces like department stores and theaters, became an icon of the modern city. For women artists like Morisot and Cassatt, however, the streets of Paris were often inaccessible. Social norms restricted their movements and opportunities, making their depictions of Paris particularly poignant.

The Paris Commune and Social Unrest

A particularly moving section of New Paris is dedicated to the 1871 Paris Commune, a brief but intense period of revolutionary struggle. Following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, Parisians rebelled against the government, seeking to establish a more egalitarian society. The Commune was crushed with brutal force, and thousands of revolutionaries were killed. This period of social unrest, which was marked by violence, hunger, and the disruption of daily life, is depicted in both the works of Daumier and photographs by Félix Nadar. Nadar’s iconic images of Paris during the Commune provide a stark contrast to the idyllic depictions of Paris in the Impressionist works, reminding us of the city’s contradictions.

The Social Divide: Paris’s Underbelly

While the Impressionists focused on the beauty of the new Paris, there was a darker side to the city’s transformation. The exhibition also brings attention to the growing social divide and the displacement of the working class. This is powerfully illustrated through Honoré Daumier’s lithographs, which offer a sharp critique of the gentrification and the consequences of Haussmann’s renovation. His works depict the struggles of the working class, who were pushed to the periphery of the city while the elite enjoyed the benefits of Haussmann’s vision.

One of the most compelling aspects of the exhibition is the inclusion of works by Félix Nadar, the photographer and balloonist, who captured images of the city during this transformative period. His photographs provide a stark contrast to the Impressionist paintings, documenting the lives of the people who lived in the shadow of Paris’s grand transformation. Nadar’s photographs, along with Daumier’s prints, serve as a reminder that while the new Paris was a place of beauty and innovation for some, it was a place of struggle and displacement for others.

A City of Contradictions

“New Paris: From Monet to Morisot” is an exhibition that captures the many contradictions of Paris during a pivotal moment in its history. It showcases a city that was both beautiful and brutal, modern and ancient, a place where dreams were built and destroyed. The Impressionists, in their own way, captured the essence of this duality. They painted the Paris that was coming to life—its wide boulevards, its bustling cafés, and its vibrant social scenes—but they also subtly hinted at the social tensions that underpinned this new city.

The struggle between progress and inequality, between beauty and hardship, is something that continues to shape cities around the world. Paris, in its transformation from chaos to modernity, offers us timeless lessons about the power of art to capture the human experience, and the ways in which cities shape—and are shaped by—the people who live in them.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to support my work without a paid subscription, consider buying me a coffee! Your support helps keep the creativity flowing. Thank you! ☕

The Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s exhibition was a journey through a city both familiar and foreign. It was a chance to see Paris not only through the eyes of the artists who loved it but also through the lens of history, as a city caught between two worlds—the old and the new, the beautiful and the broken. And in that journey, I found myself not just admiring the art, but also contemplating the stories of the people who lived through this transformation, whose lives were as much a part of Paris’s story as the grand boulevards and the shining Eiffel Tower.

As the exhibition runs until June 9, 2025, I highly recommend taking the time to visit and immerse yourself in the New Paris. Whether you're an art lover, a history enthusiast, or simply someone fascinated by the city, the exhibition offers a rich and poignant exploration of Paris’s ever-evolving identity.